Building a Great Company

22 May 2015

Good is the enemy of great. If a company faces dire circumstances, managers must change because the alternative is death. But if circumstances are good (or even okay) managers can coast along indefinitely. A good company can be lulled into a state of complacency instead of achieving greatness.

So how does a good company become great?

Greatness Defined

A team led by author Jim Collins spent five years examining publicly traded companies to determine why some companies make the leap to greatness while others remain simply good. Collins and his team published their findings in the book Good to Great.

The study only focused on publicly traded companies since their financial data is readily available. The team defined great companies as those that beat the general stock market by an average of seven times (7x) over fifteen years. This is better than double the results delivered by some of the world’s greatest companies, including Intel, Coca-Cola, and General Electric.

Special attention was paid to companies that delivered average or poor results for fifteen years, followed by a sudden shift to great results. The team’s driving question: What are the universal distinguishing characteristics that cause a company to go from good to great? Or, in the diagram at the top of this article: What’s inside the black box?

What Great Companies Do

Collins and his team observed that great companies are great because of the way they think and act. This article will discuss two findings from the study:

- The Hedgehog Concept

- The Stockdale Paradox

The Fox and the Hedgehog

The hedgehog concept comes from an ancient fable about a fox and a hedgehog. The fox is hungry for a hedgehog dinner. Cunning and skillful, the fox has several clever attack plans to choose from.

The hedgehog is less clever. It has one (and only one) very effective plan: To roll itself into a ball, exposing its needles and forcing the fox to find food somewhere else.

The fox has many plans. The hedgehog has one plan. In the fable, simplicity triumphs over cleverness. The hedgehog wins.

Hedgehogs and Business

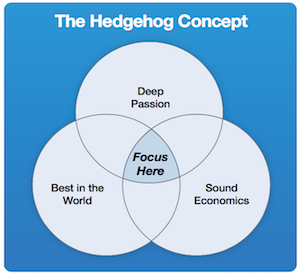

The Good to Great team discovered that great companies are like the hedgehog. Great companies focus on the one thing that they are good at. Further, great companies only fix their focus after an honest and serious examination of their strengths & weaknesses. The best focal point lies at the intersection of three interlocking rings:

- Deep Passion. What does the company feel deeply passionate about? What gives them that “I can’t believe I get paid to do this” feeling?

- Sound Economics. What will customers pay the company to do or provide? What drives the economic engine?

- Best in the World. What can the company do better than any other company in the world?

Deep Passion

Gillette was cited as a great company where employees were excited about the advanced technology in their razors. They decided on advanced-technology razors largely because they couldn’t get excited about competing in the price-sensitive disposable market.

Employees of the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) could never get excited about crunching numbers, but the idea of helping people buy homes proved exciting. Fannie Mae employees are on a heroic quest to democratize home ownership.

The Good to Great team observed that passion cannot be forced, it can only be discovered. Forcing your company to be passionate about an idea is like forcing yourself to like a particular flavor of ice cream. You either like it or you don’t.

Sound Economics

What will customers pay for? And what is the best way to measure progress toward greatness? The great companies found one metric (like profit per store or profit per employee) that every person in the company could focus on during the march to greatness.

One great company, Walgreens, chose profit per customer visit as the best economic measuring stick for their business. The decision was driven by their discovery that customers will pay for convenience, and the most convenient store locations are also the most expensive to lease & maintain. The only way to justify expensive locations: Make every customer visit as profitable as possible.

Best in the World

Investor Warren Buffett says this about Wells Fargo: “They stick with what they understand and let their abilities, not their egos, determine what they attempt.” At one point the bank decided to shut down its international operations and focus on the Western United States. Other banks, notably Bank of America, pursued every possible opportunity regardless of its fit with their skill set. The result: Wells Fargo outperformed and outgrew the much larger competitor. Wells Fargo played hedgehog to the BofA fox.

The Stockdale Paradox

Admiral Jim Stockdale was the highest ranking U.S. military officer captured during the Vietnam War. During eight years of imprisonment, he and his fellow soldiers were tortured repeatedly and forced to participate in propaganda films as “well treated” prisoners. The prisoners had no idea whether they would survive to see their families again. Stockdale survived, and after his release, the Admiral and his wife co-authored an account of his ordeal in the book In Love and War.

Optimism and Discouragement

Imprisonment is far more serious than anything most business execs will ever face. Still, the Good to Great team and Admiral Stockdale were able to draw parallels between growing a company and surviving life as a POW. For example, the Admiral observed that optimists had the hardest time in prison. Optimistic prisoners always believed “we’ll be released next Christmas” only to be let down year after year. Many optimists eventually died heartbroken in prison.

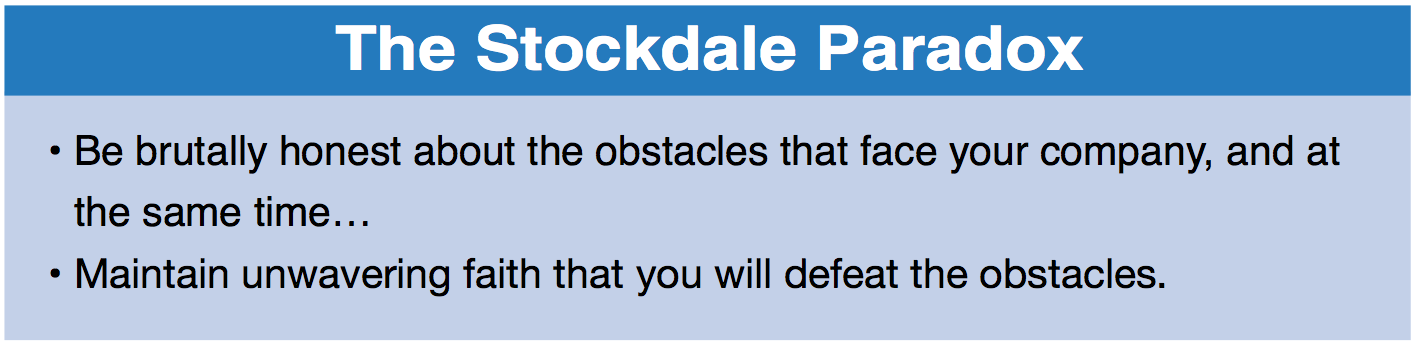

Stockdale’s policy was to be brutally honest about the situation he was facing and to deal with it directly day to day. At the same time, he maintained faith that he would prevail in the end. During the pain of the ordeal, he decided to turn the experience into the defining event of his life. Thus the paradox: He brutally confronted his reality, yet he maintained faith that he would prevail in the end.

Great Companies Respond Differently to Adversity

Collins and his team observed that companies, being made up of people, behave like people. What separates the good from the great is not whether they have difficulties, but how they deal with those difficulties. Every company faces obstacles of one type or another. But the great companies face those obstacles directly, recognizing them for what they are, while at the same time maintaining faith that they will prevail.

Stockdale Paradox Example

The banking industry became commoditized during the 1980s period of deregulation. Some banks left the industry (voluntarily or otherwise). Wells Fargo, however, thrived and grew during the upheaval. They confronted the brutal reality of deregulation and commoditization by focusing on one region of the United States and moving more of their operations to small branches and ATMs. Result: Higher profit per employee. Other banks, that did not confront changing reality, were either dissolved or acquired.

Does Technology Matter?

What about technology? Great companies are not necessarily those that spent the most on technology. This makes sense when you consider that technology is only a tool; only a bus that a company chooses to ride. If the bus is headed in the wrong direction, a faster bus will only make things worse. But if the bus is headed in the right direction, then a faster bus might accelerate the move to greatness.

Note: A version of this article was originally posted at WisdomGroup.com.