Comparing Ruby, C, and Go

11 Apr 2016

What do we learn when we solve the same problem in Ruby, C, and Go? How might the solutions differ in flexibility, readability, and performance?

The Hashrocket team presented a snake_case programming challenge during Ancient City Ruby last week. Nineteen attendees submitted correct solutions. Three of the solvers were selected at random to receive a prize: Raspberry Pi 3.

One of the solvers, Jack Christensen of Hashrocket, gave a lightning talk about his approach. The contest called for a solution in Ruby. Jack added two more languages: C and Go.

The Challenge

Here’s the challenge, as presented to the Ancient City Ruby audience:

You’ve just arrived in sunny St. Augustine, and find yourself amazed by the visionary civic planning that would result in the area in which you now stand: a street grid exactly 10 blocks square.

You’re in the northwest corner of this 10 by 10 block area, and would like to take a scenic walk to the southeast corner, while only ever moving south or east.

As you begin walking, you wonder to yourself, “how many different paths could I take from this northwest corner to the southeast corner?”

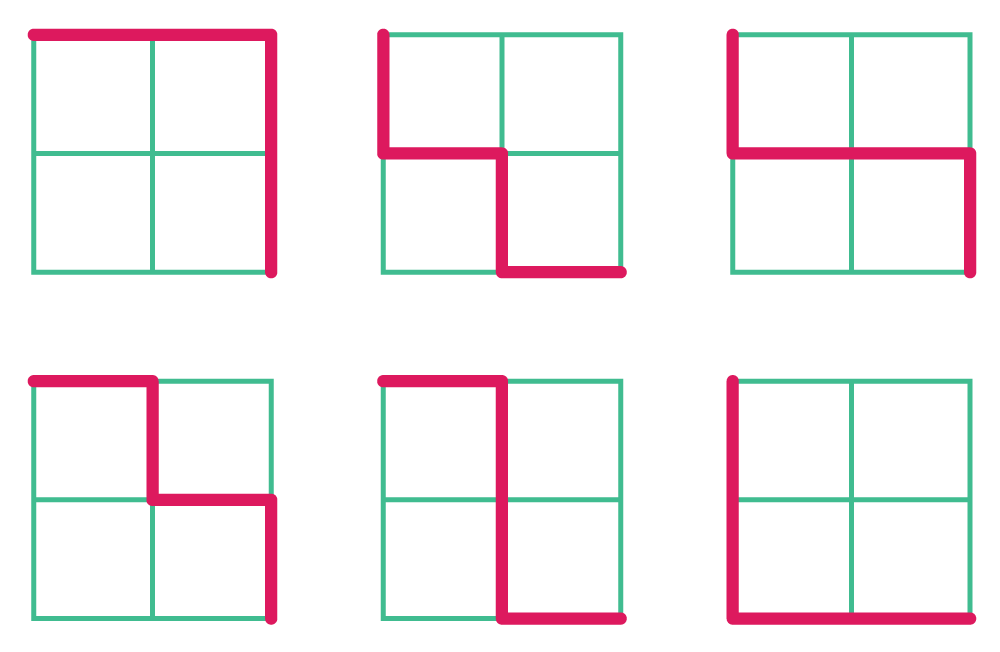

You quickly note that if the downtown area were only a 2 block by 2 block grid, there would be 6 distinct paths from one corner to the other (see the diagram at the top of this post).

So, how many distinct paths are there through the 10 by 10 downtown area?

We’ll assume that the standard compass points apply to the map: North is at the top.

Studying the Problem

Jack observed a few things about the scenic route:

-

At each intersection, there are two directions that a traveler can choose while moving from start to finish along the scenic route: south or east.

-

At the end of the walk, the traveler will have walked a total of ten (10) blocks south and ten (10) blocks east. Twenty moves in all.

Any solution that nets 10 south plus 10 east will get the traveler to the end of the route.

Data Representation

“Two choices… sounds like binary to me”, Jack observed during his lightning talk. So he decided to represent each journey as a 20-bit binary number:

-

1 bit for each of the 20 moves.

-

Let the bit = 1 for a southward move.

-

Let the bit = 0 for an eastward move.

A successful journey will consist of exactly ten “1” bits and ten “0” bits. The 1s and 0s can be in any order.

This similar to a coin-flipping problem. The flipper flips a coin twenty times, recording heads or tails after each flip. How many different ways can we flip the coin so that the end result produces exactly ten heads and exactly ten tails?

Start Small (2x2)

The binary model works with the small, 2x2 block example at the beginning of this post.

0000

0001

0010

0011 (solution)

0100

0101 (solution)

0110 (solution)

0111

1000

1001 (solution)

1010 (solution)

1011

1100 (solution)

1101

1110

1111

There are six solutions represented in binary, the same number of solutions shown graphically in 2x2 block example.

Math Solution for 10x10

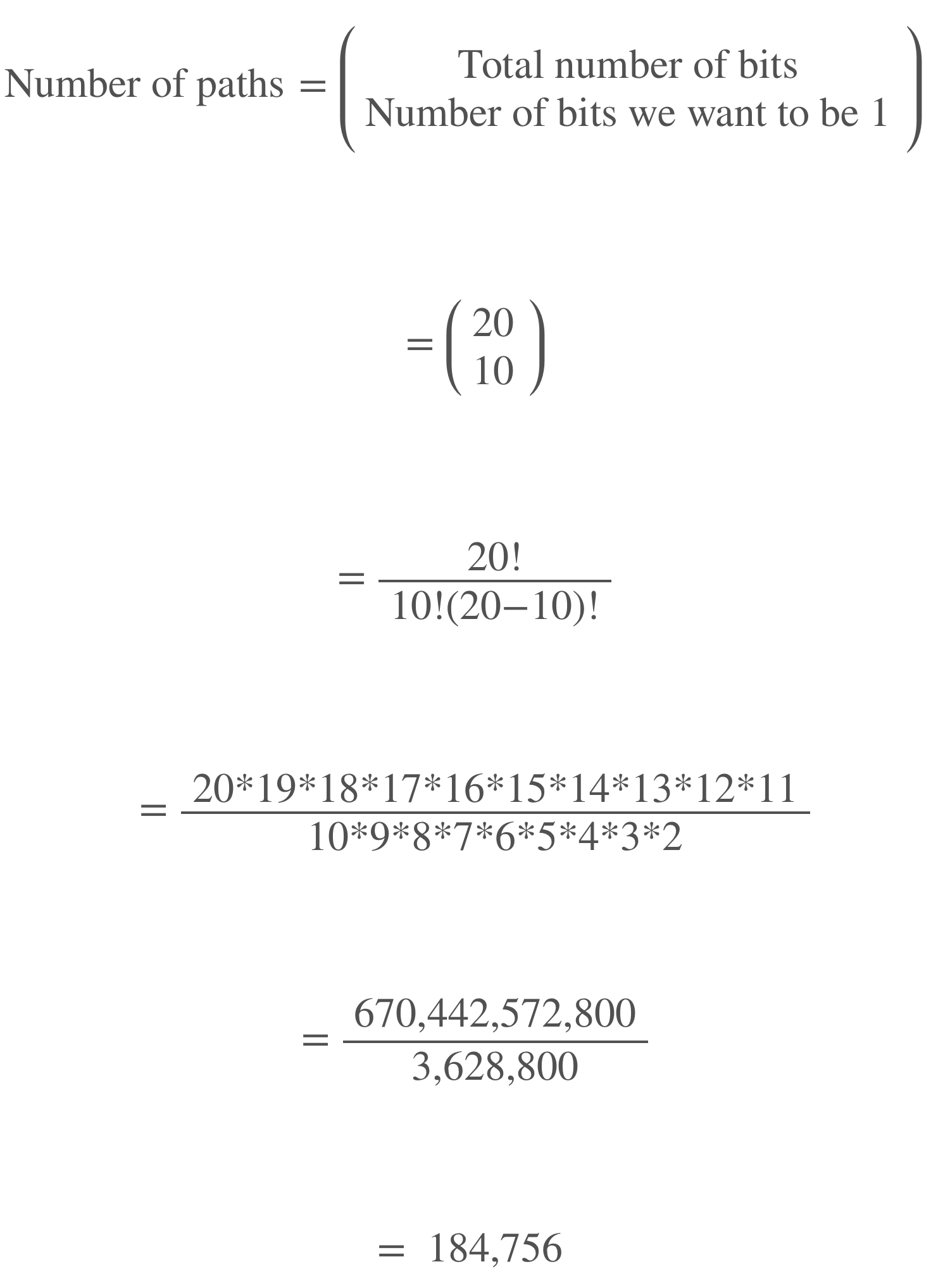

A mathematician, observing that we want to choose 10 bits from a fixed set of 20 bits, might use combinatorics:

Any correct algorithm will give us the same result: 184,756 paths that fit the constraints of the challenge.

Brute Force Solution in Ruby

A brute force solution will solve the problem by looking at every possible combination of bits, one by one. Easy for a small dataset like the 2x2 example. But for larger datasets, a brute force algorithm will consume more time.

Of course, brute force can be fun! Here’s Jack’s brute force solution in Ruby.

puts (0..(2**20)).count { |n| n.to_s(2).chars.count("1") == 10 }

This one-line program…

-

Iterates over every integer from 0 to

2**20(20-bits long). -

Converts the number into binary.

-

Converts that binary number into a string.

-

Counts the number of “1” characters in the string.

-

If the string contains exactly ten “1” characters, then that string gets counted as a solution path.

-

The final count of solution paths is printed on the screen.

Brute force!

We can use OS X’s time command to measure performance.

$ time ruby main.rb

184756

real 0m3.129s

user 0m3.115s

sys 0m0.012s

$

Ruby found the correct result, 184756, in just over three seconds.

Updated Ruby Version (14Apr2016)

In the comments below, rbhander observed that we can write the brute force Ruby solution without the chars method. It works, and it saves time:

puts (0..(2**20)).count { |n| n.to_s(2).count("1") == 10 }

Before we run the new Ruby version, let’s use the chmod command to make it executable.

$ ls -al main-nochars.rb

-rw-r--r-- 1 rth staff 59 Apr 12 00:22 main-nochars.rb

$ chmod +x main-nochars.rb

$ ls -al main-nochars.rb

-rwxr-xr-x 1 rth staff 59 Apr 12 00:22 main-nochars.rb

$

Timing the faster Ruby version…

$ time ruby ./main-nochars.rb

184756

real 0m0.567s

user 0m0.555s

sys 0m0.010s

$

The version without chars executes in 567ms, much faster than the first Ruby version. Open source rocks when we share ideas like this!

Brute Force in C

We expect C to be faster because it’s compiled and closer to the hardware. Let’s see if that’s true. Here’s Jack’s solution in C:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#define SQUARE_SIZE 10

int main() {

int64_t paths = 0;

for(int64_t i = 0; i < (int64_t) (1)<<(SQUARE_SIZE*2); i++) {

int64_t bitCount = __builtin_popcount(i);

if(bitCount == SQUARE_SIZE) {

paths++;

}

}

printf("%lld\n", paths);

return 0;

}

How long does it take to find the solution in C? First, let’s compile the program…

$ gcc main.c -o main

$

…and run it using time to measure performance.

$ time ./main

184756

real 0m0.009s

user 0m0.006s

sys 0m0.002s

$

Execution in nine milliseconds. Running close to the metal has its advantages! The C solution offers other benefits:

-

Flexibility. If you want to solve a larger square, you know exactly what constant to change,

SQUARE_SIZE. -

Readability. You can see exactly what’s going on inside of the loop. At any given time, the varialbe

pathsstores the number of paths that the program has found, whilebitcountstores the number of set bits in the current number under examination.

Brute Force in Go

And now for the brute force Go solution.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"github.com/cznic/mathutil"

)

const squareSize = 10

func main() {

var paths int64

for i := uint64(0); i < uint64(1<<(squareSize*2)); i++ {

bitCount := mathutil.PopCountUint64(i)

if bitCount == squareSize {

paths++

}

}

fmt.Println(paths)

}

Before we compile and run the program, we need to grab a math library from github.com/cznic/mathutil. Here’s how to do that.

$ go get github.com/cznic/mathutil

$

Next, we compile the program. Note that Go is particular about directory structure. Unlike with C, the source file and the executable file reside in different directories by default, even with a small Go program. Therefore, the next few illustrations will include the full path of the directories where the commands were executed on my machine.

~/Code/gocode/src/github.com/rayhightower/acr16$ go install

~/Code/gocode/src/github.com/rayhightower/acr16$

Next, switch to the directory where the new executable is located, and run it while using time to measure performance.

~/Code/gocode/bin$ time ./acr16

184756

real 0m0.015s

user 0m0.009s

sys 0m0.004s

~/Code/gocode/bin$

Same result, 184756, as expected. Execution in fifteen milliseconds. Much faster than Ruby, but not as fast as C.

Like C, this Go solution offers some advantages:

-

Flexibility. For a larger square, change the value of one constant,

squareSize. -

Readability. The loop structure makes this program easier to read than the single-line Ruby version.

-

Cool functions. For example,

PopCountUint64is a population counter, counting the number of bits that are equal to1. -

Native support for concurrency and parallelism. Not applicable in this example, but useful when we need to improve performance.

Observations

Programming challenges help to keep the mind flexible. Flexible brains are most helpful for problem solving.

C and Go, as compiled languages, will always execute faster than Ruby. Ruby, as an interpreted language, will always make it easy for developers to iterate and experiment because there’s no compile step to break our rhythm.

Gratitude

Special thanks to Ancient City Ruby for sharing a challenge that stretches the brain, and to Jack Christensen for solving the problem three ways.

WindyCityThings: IoT in June 2016

Are you exploring the Internet of Things? Then you might like the WindyCityThings IoT conference. Get the maximum return for the time you invest. Move forward on your next IoT project with confidence. Tickets are on sale now.